Photography has been the passion of many since its invention in the first half of the 19th century. Military photojournalists are always looking for new opportunities to show the world what they see or experience. Sometimes, battles can be grotesque, and other times, pictures can show the glory of a victorious nation or the defeat of the enemy.

War photography began with the Mexican-American War in 1847 and continued throughout the numerous conflicts since that point. There have been many Jewish war photographers, some famous and others as not as celebrated, with many of their images known to the public.

Robert Capa was born in Hungary and covered several wars and events including the Spanish Civil War, World War II, and Israel in 1948, and was killed while taking photographs during the First Indo-China War in 1954. He came ashore with American soldiers during the second wave of landings on D-Day, June 6, 1944. Eleven pictures survived and told the story of the landings to those back in the U.S.

Joe Rosenthal was a photographer with the Associated Press and was sent to the Pacific following the Marines on the path to Japan. The Marines invaded the strategic island of Iwo Jima that the air corps wanted for an advance air base to bomb Japan. On February 19, 1945, Marines stepped ashore on Iwo Jima, and Rosenthal was in the first wave of Marines to land.

Mount Surabachi stood 550-feet tall, and its peak was taken on February 23. Forty men from Easy Company from the 2nd Battalion, 28th Regiment, 5th Marine Division took along a flag and set up a photo opportunity for a couple of photojournalists who tagged along. Staff Sergeant Louis Lowery of Leatherneck Magazine took a picture of the event, which shows several men around an already raised flag. However, the picture didn’t satisfy the secretary of the navy, and the next day another patrol was sent up the mountain. Using a captured Japanese water pipe, five Marines and one navy corpsman were about to raise the flag. Joe Rosenthal almost missed the shot and had to take the picture without using the viewfinder. Bill Genaust, one of the other photographers in the group, stood next to Rosenthal taking a video of the historic event. It was a one in a million shot, and it was immediately sent to AP headquarters where the editor exclaimed, “Here’s one for all time!” Within eighteen hours of being taken, the picture was being distributed. It was awarded the 1945 Pulitzer Prize for Photography. In the 1950s, a bronze statue was created from the image in the photo and now stands as the U.S. Marine Corps War Memorial in Arlington, Virginia.

Another iconic image from World War II was the image of a Soviet soldier raising a flag over the Reichstag in Berlin on May 2, 1945. The photographer was Yevgeny Khaldei who was born in the Ukraine to a Jewish family. He began working for the news agency of the Soviet Union in 1936 and was attached to the Red Army for the duration of the war. The photographs he took were to document key moments of the war as he accompanied the army through many countries and cities. He saw the iconic photo that Rosenthal had taken in February 1945, and in May of that year Khaldei got his chance to capture another important moment.

On April 16, the Russian Army began the final assault on Berlin – the battle lasted until May 2. Fighting for the Reichstag was fierce, even though it hadn’t been in use since a fire damaged it in 1933. When it was captured, one of the most symbolic buildings in Nazi Germany was finally in Allied hands. Khaldei then climbed to the top of the building carrying a flag made of three tablecloths sewn by his uncle. His account of the story was that he randomly picked three soldiers nearby to help him take the photo, although Soviet propaganda said it was two handpicked soldiers. The soldiers then placed the flag while Khaldei took the photo. On May 13, the photo was published, and soon Khaldei became world renown.

During the Nuremberg trials and the Potsdam Conference both Capa and Khaldei were present and took photos of the historic events.

First Lieutenant Charles Levy of the American Air Corps was the photographer on the second atomic bomb mission. He took the famous picture of the mushroom cloud over Nagasaki (we discussed the mission in greater depth in a recent article). Another Jewish photographer was present to take pictures of the Enola Gay after the B-29 Superfortress dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

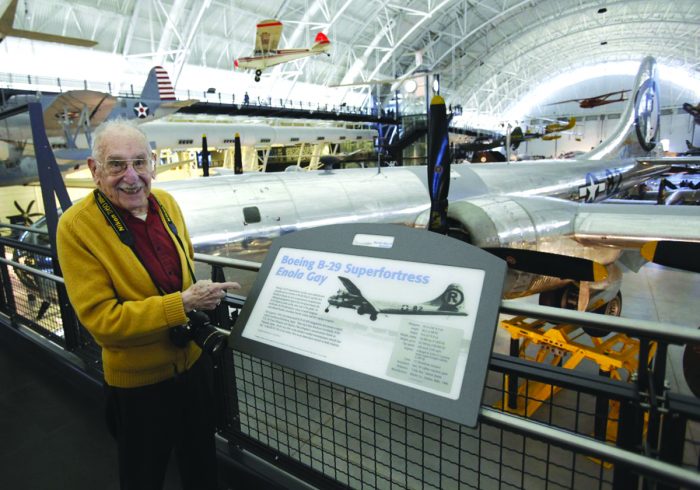

Max Desfor was born in the Bronx and taught himself the art of photography while working for the Associated Press as a courier. Soon after the U.S. entered the war, Desfor tried to enter the navy but was rejected based on age and other factors. Still, he managed to get an overseas assignment with the navy for the AP working for the staff of Admiral Chester Nimitz. In August 1945, he was called to the island of Tinian to photograph the Enola Gay as it was landing. The picture is currently on display next to plane itself at the Udvar Hazy National Air and Space Museum in Chantilly, Virginia. Less than a month later, Desfor was on the USS Missouri to take pictures of the Japanese surrender.

Being a frontline photojournalist can be a dangerous living, and many were wounded or killed since military photography became an occupation. Pictures can tell a story that words can’t necessarily depict. The men described in this article were among the best. Their work shows the dedication to the job at hand. While the public may know their pictures, the men who took them are often forgotten heroes.

Categorised in: Forgotten Heroes